A groundbreaking, no barriers new healthcare model: The Yapatjarrathati Projects

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is one of the most prevalent neurodevelopmental disorders nationwide—affecting 3 per cent to 19 per cent of children, based on diverse studies—but it remains chronically under-recognised due to the cost, length and inaccessibility of diagnostic assessments.

This has made timely diagnosis particularly challenging in remote communities, where local health practitioners often lack relevant expertise. In these communities, children who are suspected of having developmental issues due to prenatal alcohol exposure are instead referred to specialist clinics, predominantly located in the capital cities. This is cost-prohibitive for many families, with support mechanisms dependent on a positive diagnosis, and access to such clinics is often locked behind waitlists of up to three years. Additionally, visits to medical offices can, in some cases, break the cultural protocols of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Because of these factors, children from remote communities often miss out on the sorts of early interventions that could otherwise provide long-term functional improvements.

Research led by a team of experts from Griffith University and conducted in collaboration with Gidgee Healing, an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, has created a new model of holistic, culturally responsive healthcare that celebrates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people strengths. The Yapatjarrathati project, named by Kalkadoon Elders and meaning to ‘get well’, has addressed key barriers to service access in two main ways:

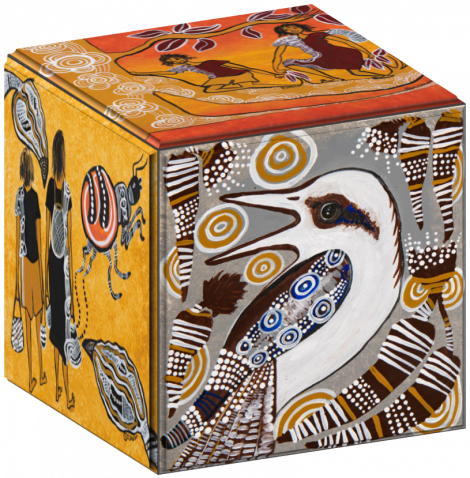

1) Creating a new care model (named the ‘care journey’ by the local community), which includes a six-tiered assessment, known as the Tracking Cube. This model integrates with everyday health checks and clinical decision-making tools, helping to triage children to support pathways.

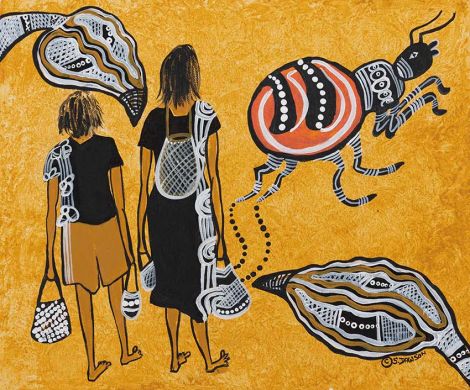

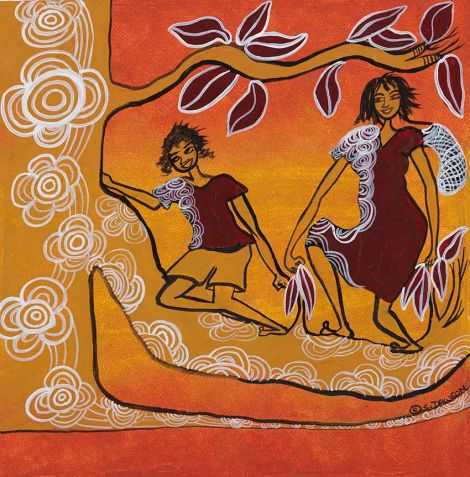

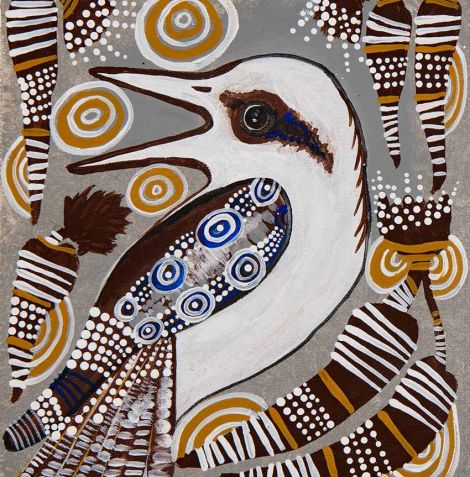

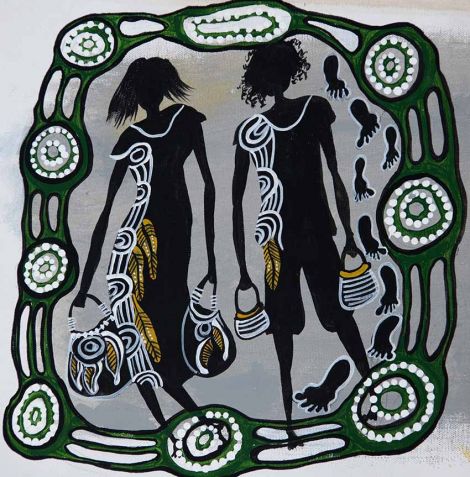

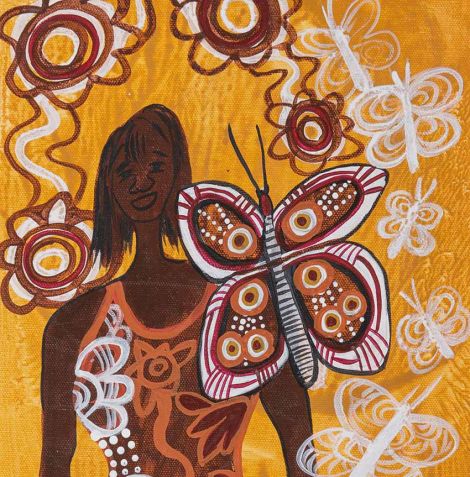

2) Implementing a Dreamtime story and associated artwork (written by a rural GP from the Kalkadoon, Waanyi, and Ganggalidda Nation groups, Dr Marjad Page and illustrated by an artist from the Eastern Aranda Nation group, Ms Shirley Dawson) that explains the care journey and facilitates communication between healthcare practitioners and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers.

This new healthcare model has effectively addressed the lack of local diagnostic services, and every child in the local Gidgee area is now tracked, allowing for early support to be offered as needed. Providing local care has also removed the barriers created by cost of travel and lengthy waitlists. The success of this new model has been demonstrated by the positive response from caregivers using the Gidgee Healing service: ‘The experience that we've had has just been really good ... I guess the last eight months, it's been really hard for myself and my husband because we don't know what's going on. ... me personally, I was like "Am I doing something wrong?" ... it's been so difficult. Just to have an outcome now, I guess, and support. They've been nothing but supportive and it's been really good.’

Since the Yapatjarrathati project began, 670 children between one and17 years old have started using the Tracking Cube. After discussion at the Rock meeting—another culturally appropriate healthcare mechanism involving interprofessional case discussions—485 children entered at least one support pathway. By July 2022, 46 children had commenced the FASD assessment process, and 14 children were diagnosed with FASD locally.

Through interactive, case-based learning and problem-solving, this research has resulted in the first training of its kind in Australia, designed to support remote primary healthcare providers in screening for, diagnosing and managing child neurodevelopmental impairments in a culturally responsive manner. Where previously these practitioners had found it challenging to work with children with developmental delays, the newly upskilled Gidgee Healing staff have reported much more positive experiences. 'With using the Tracking Cube, it just helps support the children to get the right support. There was a family with three kids that just recently came through the tiers. The mum kind of knew that was something not right and the results confirmed everything for her. She’s over the moon and as a health worker that was really, really rewarding to think there’s one family already on track.’

The research also informed the recommendations of a 2019 Australian Senate inquiry, which focused on better understanding the burden of FASD and why it continues to be nationally under-recognised. Inquiry recommendations included increased funding being directed towards national trials of the six-tiered assessment in primary care, particularly in rural and remote communities.

Local Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services in the neighbouring Normanton, Doomadgee and Burketown sites in Queensland have now adopted this new healthcare model, and local healthcare staff are being trained in the use of the Tracking Cube. This research was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health: Drug and Alcohol Prevention and Early Intervention: Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Diagnostic Services and Models of Care Grant (H1617G038). Other consortium members contributing to the research include the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service, North West Hospital and Health Service, Sunshine Coast Hospital and Health Service, The University of Queensland, The University of the Sunshine Coast and the Queensland Child and Youth Clinical Network.

The research engagement and the patented Tracking Cube created as part of these projects have been supported by Griffith Enterprise.

Associate Professor Dianne Shanley

Griffith Centre for Mental Health and School of Applied Psychology