Recently, a colleague and I confessed that when we feel overwhelmed by our inexhaustible to-do lists, we procrastinate by scrolling through social media. Psychologically, procrastination is a form of avoidance. The more anxious we feel about our work, the more likely we are to postpone with something mundane. I procrastinate a lot.

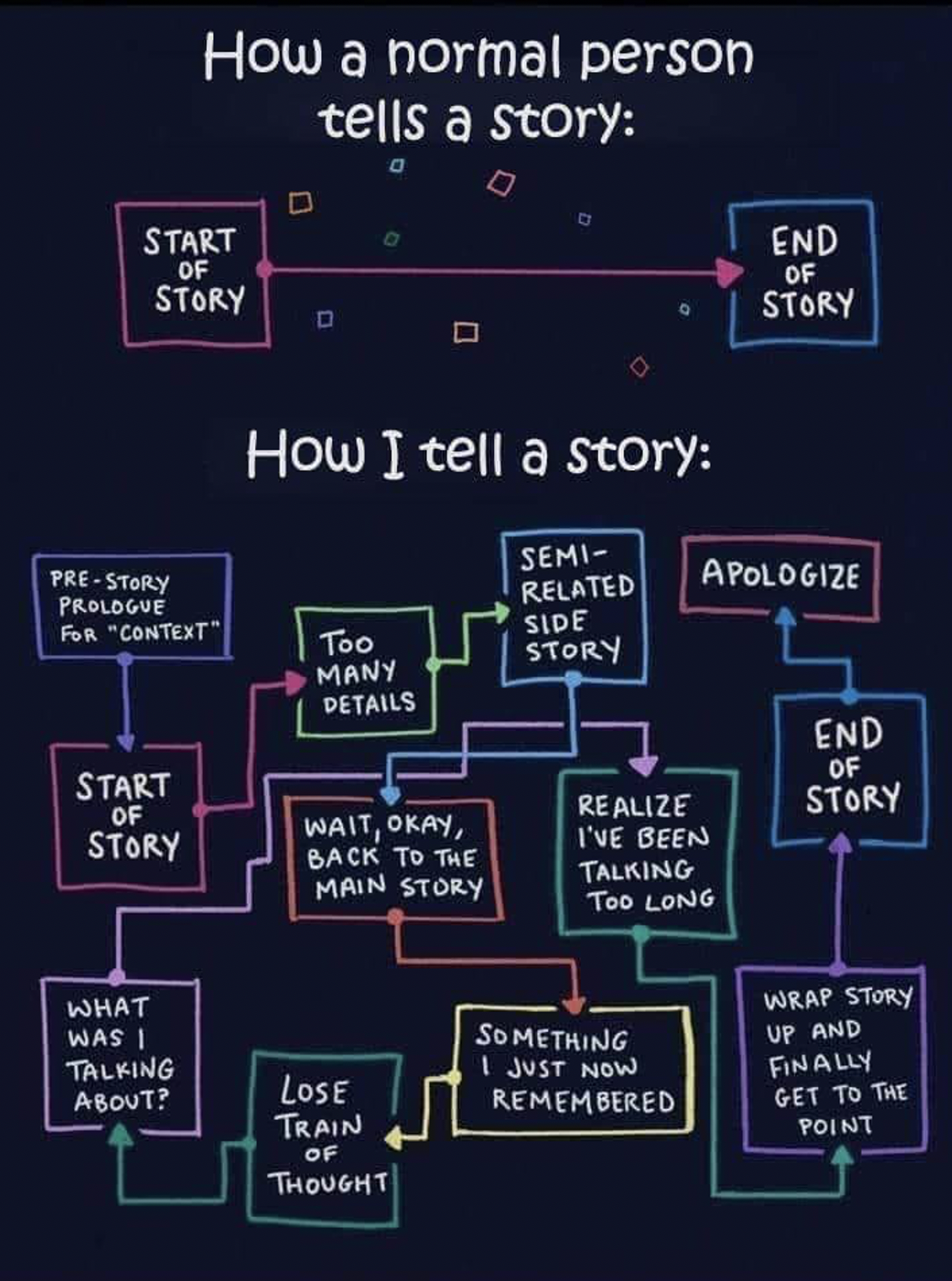

But I know I’m not alone. Increasingly, it feels we seek banal distraction from the exhaustion of working life in 2022. The other day, however, this meme made me pause doomsday scrolling for a second.

It reminded me that the complex issues of sustainability need the qualities of good storytelling – persuasive communication, collaboration, action, and courage – to have impact.

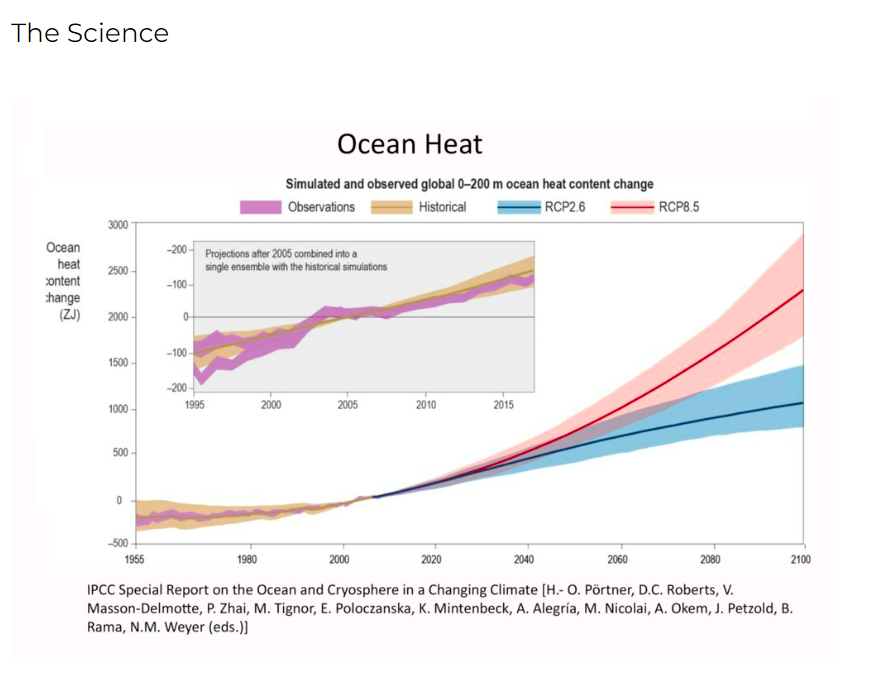

For Sustainability Week at Griffith this year we held an exhibition featuring artist Alisa Singer. Singer’s Environmental Graphiti work is inspired by the science of climate change. Using graphs, charts, and data Singer turns the facts of climate change into vibrant digital images.

Singer’s work, "Ocean Heat" (above), featured on the cover of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report from Working Group 1 (2021), which concluded that Earth is “warming at a rate without precedent in at least 2000 years, possibly longer”.

Most of us now accept the facts of climate change, not just because objective science proves them but because we experience them. It can be tempting to play Wordle, Like, LOL, or unsubscribe instead because it is all just too much. Too confronting. Too hard. However, Singers’ images force you to look, not just see. Singer’s art shows us what the facts mean and confronts us with reality. For me, her work tells a story as powerful as the IPCC reports.

For almost thirty years, I have maintained dual careers in academia and the creative industries where I practice as a dramaturg. I help playwrights create new performance works and my knowledge of story has been one of the most useful skills for my sustainability work. I have come to view sustainability as the core organisational narrative we all share – no matter what our Business As Usual – because we are all key players in the Anthropocene, as John Green (2021) reminds us “…there are no disinterested observers; there are only participants…”. My sustainability work tries to connect all kinds of stories to create a common thematic purpose that speaks to staff, students, and the wider community.

Many workplaces now recognise the importance of critical and creative thinking and problem solving but how many understand why creativity is so important to the core issues of sustainability like climate adaptation or climate risk and mitigation? An organisation’s narrative, the stories it tells about itself and others, is inseparable from its sustainability agenda and obligations. Stories aren’t just about change, they are vehicles for change since: “People use stories to reflect on the past, make sense of the present, and speculate on the future” (Almani et al, 2016).

But who is telling the story is crucial.

Indigenous Australians have been sharing knowledge and understanding about Caring for Country through stories for thousands of years. Yet we are only now starting to listen. How the story is told is also important because we are more likely to remember a good one. Author Don Watson, for example, highlighted the failure of fire managers to adequately capture the devastation of the 2009 Black Saturday fires in Victoria. He explained how the Royal Commission heard about “messaging” the public on the “likely impact” and “big learnings” of fire management. But: “Telling people requires language whose meaning is plain and unmistakable. Managerial language is never this” (in Griffith, 2021).

However, we can’t all be award winning writers, so how do you tell your sustainability story for maximum impact and what are the creative skills that can help address the challenges of sustainability? Here are two key examples drawn from writers and playwrighting:

So how to tell a story? Use "What if?"

The meme above isn’t accurate because most people (‘normal’ or not) tell a story like the bottom half. As a dramaturg I help writers find the most direct route. Sometimes, when I teach playwrighting, I use novelist Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Rules for Writers including:

- “Start as close to the end as possible”

- “Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such a complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves should cockroaches eat the last few pages” and

- “Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them in order that the reader may see what they are made of”

Above all, creativity starts with asking ‘what if?’. What if Romeo is late meeting Juliet? What if we could fly to the moon? What if humanity wipes itself out?

John Green (2021) reminds us that it is our own narcissism that makes us think that the world would be a worse place without us:

Humans are a threat to our own species and to many others, but the planet will survive us. In fact, it may only take life on Earth a few million years to recover from us. Life has bounced back from far more serious shocks ... I know the world will survive us – and in some ways it will be more alive. More birdsong. More creatures roaming around. More plants cracking through our pavement, rewilding the planet we terraformed. I imagine coyotes sleeping in the ruins of the homes we built. I imagine our plastic still washing up on beaches hundreds of years after the last of us is gone.

We may well sense the end is nigh, but we have the skills, knowledge and capacity to change the present, and it is only by changing the present that we can affect the future. We need to ask: what if it floods again, and again, and again? What if it stops raining? What if it reaches over 50 degrees every summer? What if it doesn’t get any better? We need to use our imaginations to improve the present and the future.

And so we need to collaborate

Interdisciplinarity and collaboration are crucial to sustainability impact. However, the embedded hierarchies of many workplaces can make teamwork superficial or ad hoc rather than consistent and meaningful. In theatre, collaboration is a process of genuine engagement where everyone is makes equally important contributions. Without performers, designers, technicians, stage managers, directors, writers, dramaturgs etc. the show literally doesn’t go on. This is one of the strongest lessons I have learnt from practicing dramaturgy:

True collaboration, dramaturgical collaboration, is not debate (or persuasion, diatribe, or any arena of rhetoric), not barter, territorial dispute (mine, yours), hierarchy (my decision), sitting at the same table, or in the same room… true collaboration is a verb not a noun, a process of engagement, a map more than a destination. The process fosters a community of makers, who engender a shared vision, which in turn fuels individual creation. A single artist, working alone, cannot achieve that same vision and the accompanying discoveries (Thomson , 2003).

Of course, there are egos in a rehearsal room, just like in any workplace. There are challenges and challengers; compromise and negotiations; debate and demands. But the sheer process of having to create something for public performance – something that must be shared and seen to even exist – creates a sense of community like nothing else.

The complex, interconnected problems of environmental change also needs this collaboration and sense of community. If, as a species, we have colluded to destroy our world, now we must collaborate to survive, and storytelling is one of the most important tools we have for sustainability impact in our workplaces and communities because it allows everyone to participate equally, independently, and collaboratively:

Stories are powerful. We use them every day… [and] you can leverage storytelling to create opportunities for people in your organization to arrive at their own learning moments about sustainability, where they begin to think critically about what it means for them and for your organization (Amlani et al, 2016).

So stop scrolling. Just for a second. And start asking: What is my organisation’s narrative? Who is telling the story? What part do I play in it? Does the narrative capture the diversity of people it's about and who it's for? How can the story get better? How does it contribute to a much bigger story about building a fairer, more sustainable world?

.

REFERENCES

John Green. (2021) The Anthropocene Reviewed: Essays on a human-centred planet. (London: Ebury Press)). 5. 17. 19

A. Amlani, S. Bertels, and T. Hadler. Storytelling for Sustainability. Embedding

Project. (2016). Online: https://www.embeddingproject.org/

Tom Griffiths. (2012) ‘The language of catastrophe’. Griffith Review: Surviving. (35). Online: https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/the-language-of-catastrophe/

Lynn M. Thomson. (2003) ‘Teaching and Rehearsing Collaboration’. Theatre Topics. (13.1, March). 118.

Tom Griffiths. (2010). ‘A humanist on thin ice’. Griffith Review: Prosper or Perish. (29.). Online: https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/a-humanist-on-thin-ice/

Dr Saffron Benner

Saffron is a currently Griffith's Sustainability Manager and has over twenty years’ experience as a dramaturg, working with many award-winning artists and companies including Queensland Theatre, La Boite Theatre, Tasmanian Theatre Company, Australian Theatre for Young People, The Good Room, Frankston Arts Centre, Playlab, Debase Theatre and Backbone Youth Arts. She devised and taught Griffith's only course in Dramaturgy (2005- 2005) for the Bachelor of Creative Industries and was a Research Fellow for Griffith’s Centre for Public Culture and Ideas (2008) investigating cultural value, cultural economics, creative practice and knowledge. She was Executive Director of Playlab (2008 – 2010) and the National Arts Education Editor and feature writer for Lowdown Magazine (2008-2010).

Professional Learning Hub

The above article is part of Griffith University’s Professional Learning Hub’s Thought Leadership series.

The Professional Learning Hub is Griffith University’s platform for professional learning and executive education. Our tailored professional learning focuses on the issues that are important to you and your team. Bringing together the expertise of Griffith University’s academics and research centres, our professional learning is designed to deliver creative solutions for the workplace of today and tomorrow.