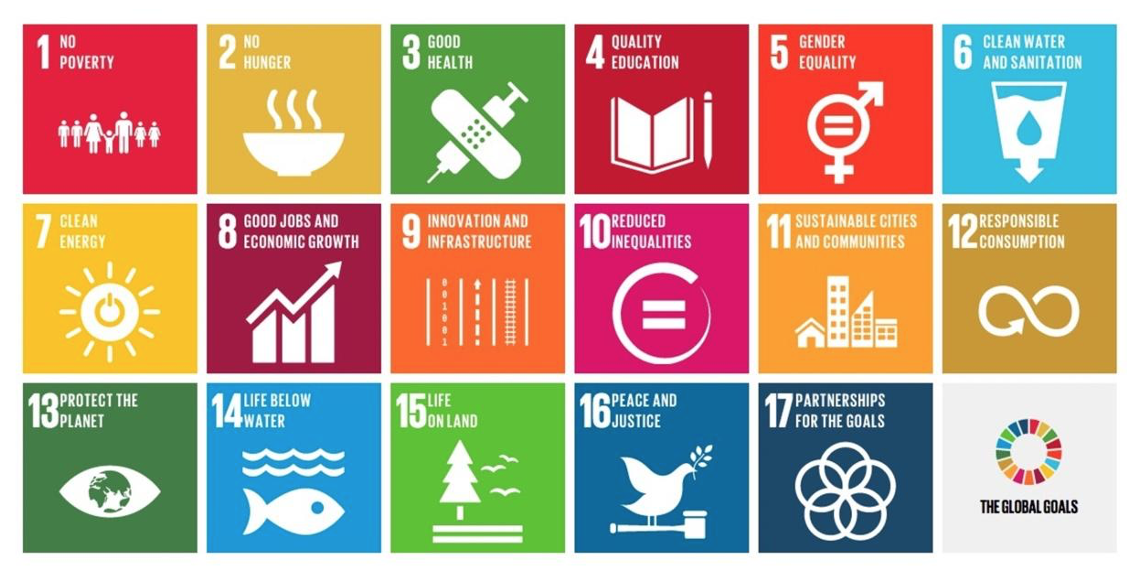

In 2015, all 193 member states of the United Nations (UN) signed up to ‘Agenda 2030’ – an ambitious global agreement to pursue sustainable development and reach a new economic equilibrium by the year 2030. This transformational agenda was framed around 17 goals with 169 targets – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

To paraphrase the UN, it was ‘a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity, that also sought to strengthen universal peace in greater freedom’. Ban Ki-moon, the UN Secretary-General at the time, stated: “It is a roadmap to ending global poverty, building a life of dignity for all and leaving no one behind. It is also a clarion call to work in partnership and intensify efforts to share prosperity, empower people’s livelihoods, ensure peace and heal our planet for the benefit of this and future generations.”

The SDGs succeeded the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) which between 2000-2015 had shaped a global effort to tackle extreme poverty and hunger, prevent deadly diseases, and expand primary education to all children, among other development priorities. While the MDGs were focused on improving outcomes in developing countries, the SDGs elevated the UN’s ambition to a universal level. They would tackle the big challenges faced by the whole world, exempting no one from action and leaving no one behind.

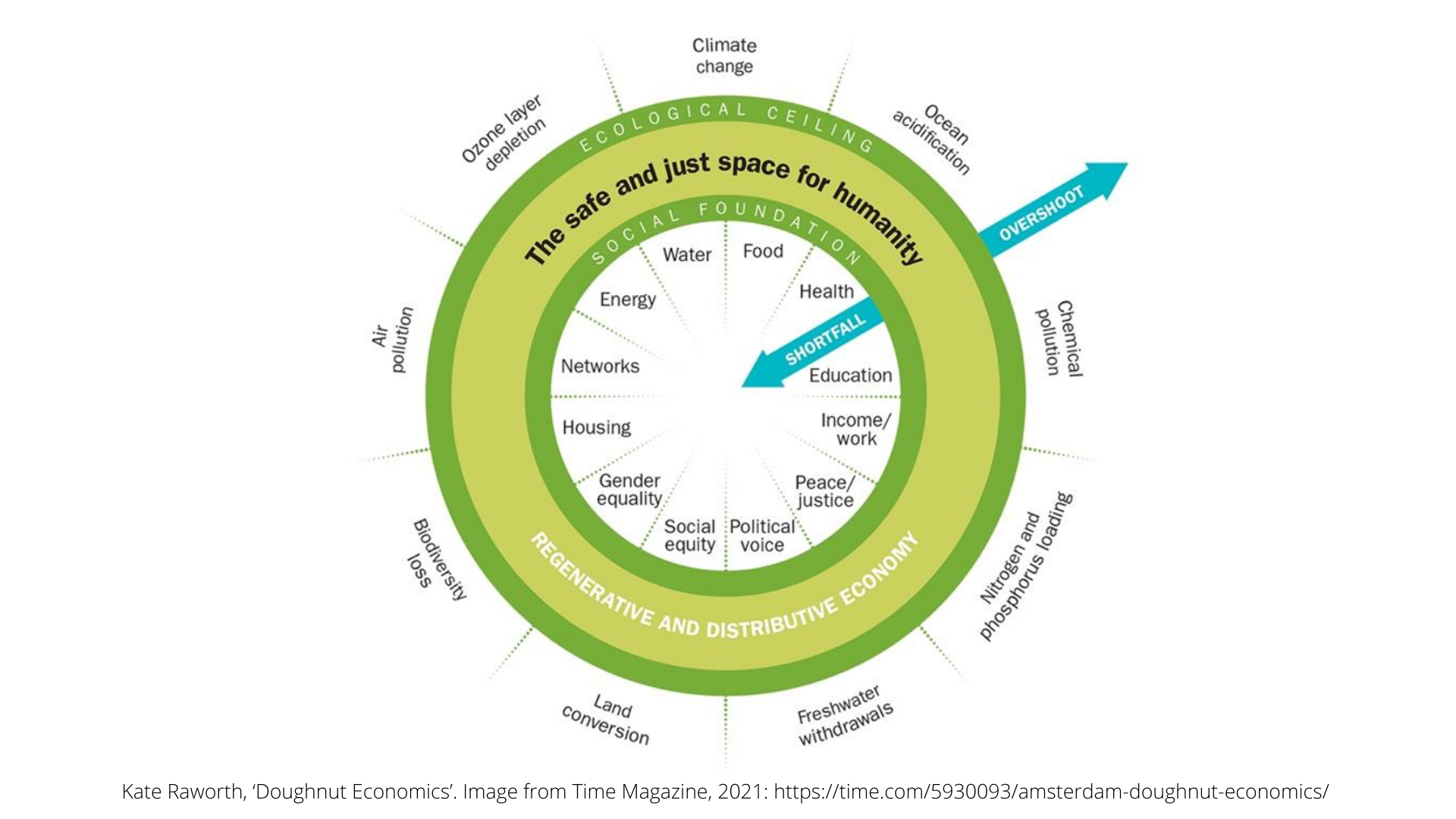

The SDGs represented a bold step forward in global cooperation. Beyond the profound step of securing universal support for the things we, as a civilisation, need to get right (we’ll come to delivery later…), the SDGs were also significant in their holistic and interconnected design. Holistic, in that they provided a multi-dimensional results framework for societal success in contrast to the narrow (and often misleading) metric of GDP. Yes, economic factors remained present and essential, but they sat within a set of metrics that spoke to the broader prospects and wellbeing of people, places and planet. Interconnected, in that the SDGs explicitly recognised that the success of any one outcome – be it economic, social, environmental or political – is bound up with the success of others. The framing of ‘trade-offs’ had been flipped to the language of ‘interdependence’ – no trivial shift. Indeed, the adoption of the SDGs has gone hand-in-hand with a renaissance in economic thinking and the challenging of many orthodoxies – from ‘Doughnut Economics’ to ‘Modern Monetary Theory’.

From a global agreement to (some) common currency.

Since their adoption in 2015, the SDGs have diffused out from the UN and become a common currency for actors with an active interest (or associated risk) in sustainability and progressive agendas. Across sectors, and around the world, the goals (if not their specific targets) have become a compass and register for myriad strategies and KPIs.

This has enabled a shared, if emergent, way to articulate and account for ‘blended value’. Be it: ESG reporting, stakeholder governance models, well-being economics, CSR strategies, or balanced business scorecards, the SDGs are fast becoming a go-to conceptual anchor and means to communicate performance for any entity in the business of impact. While ‘global’ in orientation, the SDGs have become equally relevant and useful for direction setting at the regional, city and organisational level.

With all this said, the language of the SDGs still sits within certain bubbles and has largely failed to capture the public imagination. So, while the SDGs have traction with most government agencies, boardrooms, corporate leaders, investors, purpose-led businesses, social enterprises, philanthropists and non-profits, they mean less in the daily lives of most people. Start a conversation about the SDGs down your local café or pub, and you will likely receive blank looks.

This may not be an issue. It could be that the SDGs are still finding their way into the mainstream, and that their progression through a growing number of advocates will soon see them arrive in the public discourse. Also, issues and individual goals can be elevated without the overarching framework needing to be front and centre – we see this happening with issues such as climate change and gender equality, to name but two. However, while the SDGs may not need to be front of stage to foster progress on specific issues, their dilution and lack of visibility becomes more problematic in light of the fact that we’re not on track to be where we need to be.

Ambitious goals require different ways of working…

This gap between aspiration and delivery needs further exploration. Like the MDGs before them, while the SDGs have, and are, undoubtedly generating gains, they are also falling short on their own ambition. On current trajectories the SDGs will not be achieved by 2030[1], leaving humanity exposed to a range of systemic risks and unknown consequences. We should note that this isn’t simply a matter of delay, as many of the threats that the SDGs seek to address are time critical and have irreversible tipping points. Climate change, acidification of the oceans, biodiversity loss, and the degradation of other life-supporting ecosystems are both urgent and existential challenges.

Mirroring the lack of popular awareness and buy-in, the lack of investment in the SDGs is often cited as a key inhibitor of their advancement. In 2019, the UN stated that the SDGs were being undermined by a financing gap of US$2.5 trillion dollars a year[2]. A survey conducted in 2020 by Standard Chartered amongst the world’s top 300 investment firms with total assets under management (AUM) of more than USD50 trillion found that only 13% of their investments were linked to the SDGs.[3] But given the complexity of the task, is it too easy to point to the lack of investment as the primary blocker to progress? Yes, resourcing is always part of the mix, but if COVID has taught us anything it is that there is money available when there is a clear need and application. Could it be that the financing gap is a symptom and not a cause, and that there are other factors holding us back?

Beyond the lack of awareness and investment, self-interest undoubtedly creates a significant barrier to change. As we have seen with the growth in wealth inequality during the COVID pandemic, crises can work well for those with wealth and power.[4] These groups, individuals and organisations also have a disproportionate level of influence and may use it to sustain their advantage, through maintaining the status quo, despite the consequences outside of their direct experience and lifetime. In addition to an awareness and financing gap, there would seem to be a values gap as well.

Fatalism surely also plays a role. Be it expressed through individual disempowerment in the face of such overwhelming issues, institutional caution and inertia, fear of failure, ‘techno-optimism’, or abdication of responsibility to market mechanisms; there are many good reasons why we may feel disinclined to dare to shape a safe and sustainable future.

To this point, it is perhaps fatalism that provides the biggest barrier to the majority of us more actively pursuing the SDGs, and the world that their achievement would represent. While the SDGs are clear on what we need to do, they simply leave too much uncertainty on how to do it. And if we don’t know what to do – coherently, collectively and at a convincing level scale – it also makes more sense why the investment isn’t flowing to where it needs to be.

While the SDGs provide us with direction, they also present us with problems which are categorically different in their nature to what we’re generally used to solving at an organisational, departmental or community level. ‘Planning’ our way into addressing these complex challenges simply won’t work; no strategy will resolve entrenched disadvantages and structural inequalities, or rebalance the economic system.

To respond to these ‘grand challenges’, we need approaches which are comparable in scope, scale and sophistication. Approaches that help us organise and respond in ways which no single entity, sector or stakeholder group can address on their own. Approaches that are intentionally experimental and which enable us to foster ‘innovation and collaboration pathways’[5]. Somehow, we need to catalyse coherent, but distributed and decentralised, responses that incorporate all the levers and assets that we have – technologies, markets, regulation, investment, institutions, innovation, civil movements and stories for what could be possible.

Mission-led innovation – a mindset and approach for our times

‘Mission-oriented’ or ‘mission-led’ approaches are designed with these attributes in mind. Mission-led approaches typically embody ambitious, goal-driven, and multi-stakeholder efforts to create solutions that address pressing societal challenges, needs and opportunities (Mazzucato, 2021). The most often quoted ‘mission-led approach’ is the moonshot. In the late 1950s, various countries engaged in a global challenge to take humans into space. The moonshot mission was established when the US President (JFK) set out a bold goal: “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

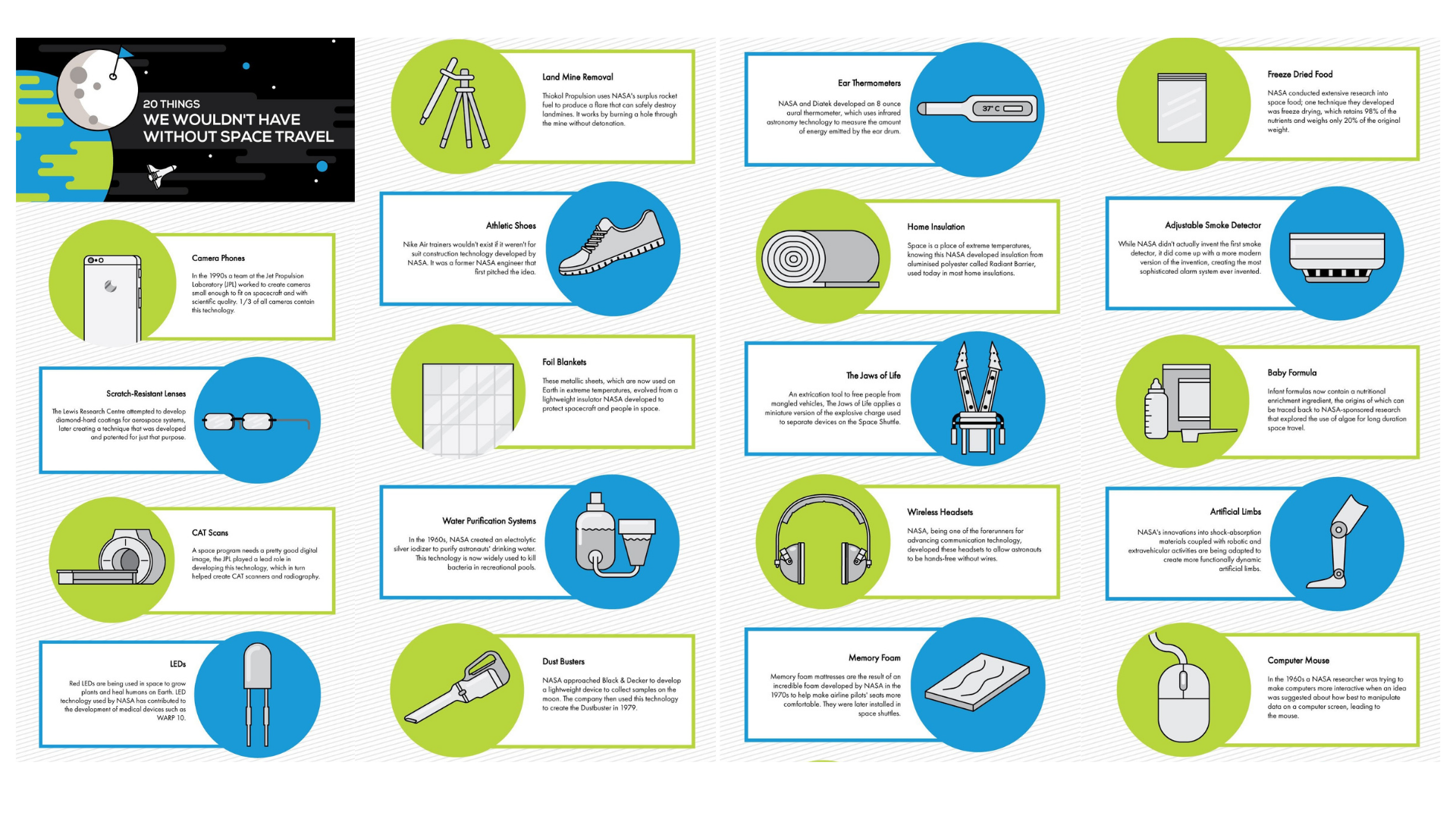

This mission required innovation and genuine cooperation across diverse industries, sectors, geographies and groups. At one point more than 300,000 people working in more than 20,000 organisations across 80 countries, were taking risks and actively experimenting to do something that had never been done before.[6] While the moon-shot was eye wateringly expensive, its spill-overs and ripple effects are still creating value today – this infographic published on Visual.ly gives some examples.[7]

While our current challenges are arguably not as clear cut as the ‘moon-shot’, they too require bold goals and ‘focused but broad’ innovations to shift current trajectories.

Mission-led approaches provide us with an architecture to conceptualise and orchestrate movements for intentional, systemic and structural change. Around the world, they are increasingly being used to this end, such as the city of Manchester’s goal to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2038.[8] In Sweden, the national innovation agency – Vinnova – has adopted the mission-led approach as its underpinning mode of practice.[9] In Australia, CSIRO is embarking on 12 missions of national significance, that range from the advancement of hydrogen-based energy to drought resilience.

Much of what’s involved in mission-led approaches is relatable and transferable from other domains. The work is less about dense technical theory and new tools, and more about a mindset that is able to hold multiple levels of intention, embody adaptive learning and leadership, and work practically within a systems context while upholding coherence, connectivity and communication across different sectors and cultural settings. Underpinning this all is a conviction in purpose and a willingness to shape the unknown future towards a preferable one – for the sake of this article, the SDGs.

Critically, the primary mode of acting within mission-led efforts is experimental – and it is this which fundamentally separates these approaches from conventional planning and programmatic work. We don’t know what to do or what will work, so we must act in cycles that propose, test, learn and adapt. Mission-led approaches are also no substitute for subject matter expertise. Doing new and difficult things requires high levels of competence, and the right people in the right roles. Indeed, a key rationale of the multi-stakeholder and cross-sectoral aspect of mission-led approaches is that complex challenges require navigating coherence across diverse organisations doing work that they excel in or have control over. In such approaches governments and public sector organisations can become key to growing the innovation infrastructure that ‘holds’ the direction and draws together the coherent pathways towards bold goals.

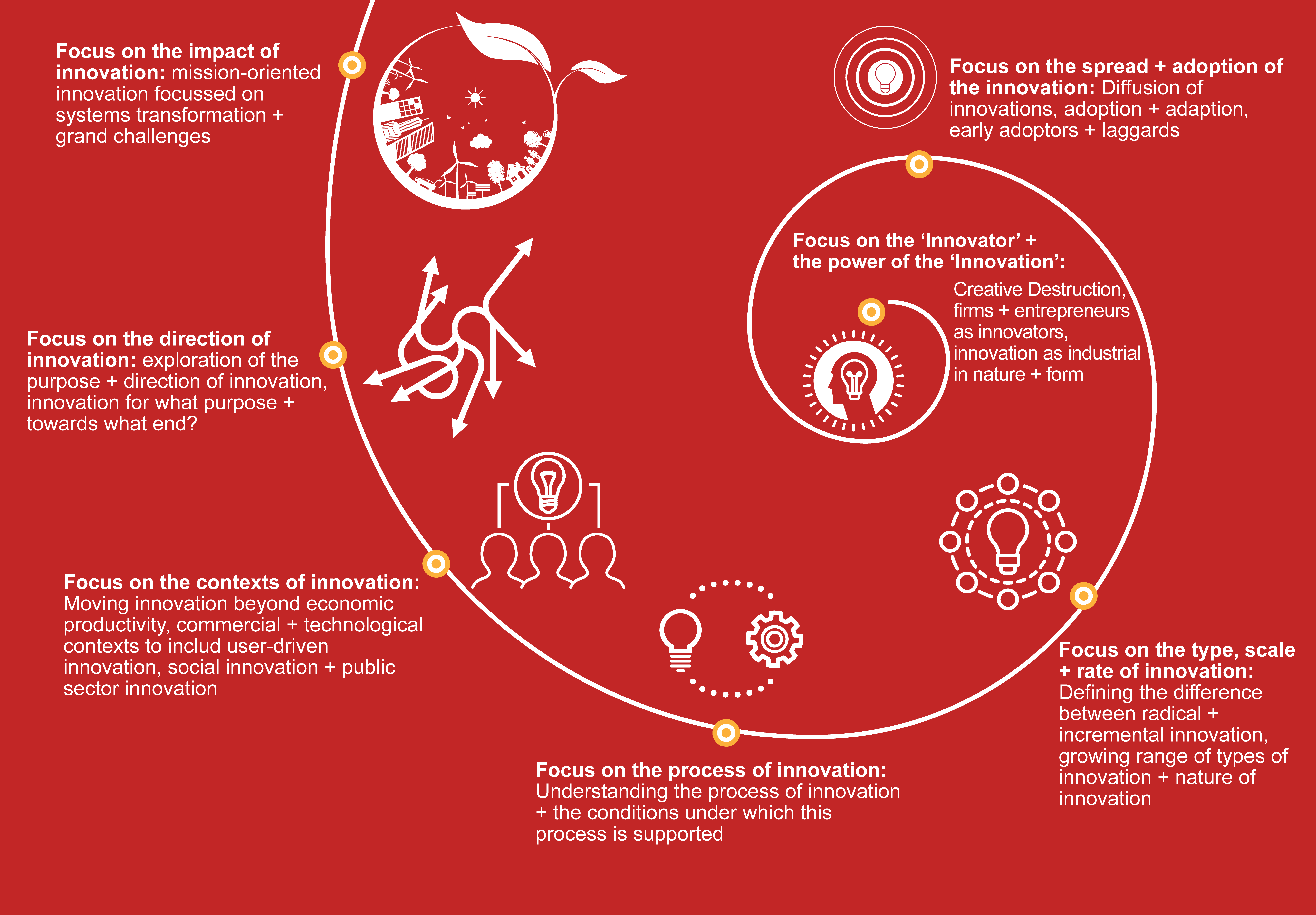

Outside of individuals and actors, mission-led approaches also demand that we think about how we create enabling environments for innovation and action. Thinking and practice around the development of innovation ecosystems is well developed across jurisdictions, but what does it mean to calibrate these systems to enable a broader range of actors towards specific and systemic goals? This isn’t so much a departure from how we have conceptualised and fostered innovation up until now, but a further layering of how we can breakthrough frontiers and create new value. This graphic by Ingrid Burkett at Griffith University’s Centre for Systems Innovation outlines how this evolution of innovation thinking and application has played out – mission-led innovation can be understood as the most recent step in a dynamic tradition.

Regardless of where you live or work, the ‘grand challenges’ of our time will affect you. So, what can you do to shift your mindset, and those around you, to face them? Will you advocate for bold goals and experimental approaches? Are you prepared to countenance structural and systemic change? Do you ‘dare disturb the universe’? How will you contribute to shaping a safe and sustainable future?

REFERENCES

[1]https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/

[2]https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/dsgsm1340.doc.htm

[3]https://www.sc.com/en/insights/50-trillion-question/

[4]https://www.ft.com/content/747a76dd-f018-4d0d-a9f3-4069bf2f5a93

[6] Mission Economy, M Mazzucato, 2020

[7]https://visual.ly/community/Infographics/science/20-things-we-wouldnt-have-without-space-travel

Centre for Systems Innovation Co-Directors

We find ourselves at a unique juncture of change, challenge and opportunity. Climate change, technology, the future of work, inequality, environmental strain, social unrest. We need new, holistic solutions, and regenerative change to rise to these challenges and opportunities. We have now adopted a mission-led approach to our research and development activity, which we will continue to evolve as we experiment and learn. We believe experimentation and innovation are central to achieving our goal and needed in all sectors, contexts and places. Through our work, we seek to amplify the practice of impact-led innovation, and enable change at the individual, organisational and systems level

Are you in? Visit us here

Read more about Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation’s mission-led approach to research and development here

Professor Ingrid Burkett

Professor of Practice Alex Hannant

Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation’s Mission-Led Mapping Re:Treat

Put your name on the waitlist for the Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation’s Mission-Led Mapping Re:Treat. A two-day intensive deep dive on how to design, implement and measure mission-led innovation strategies and movements.

Professional Learning Hub

The above article is part of Griffith University’s Professional Learning Hub’s Thought Leadership series.

The Professional Learning Hub is Griffith University’s platform for professional learning and executive education. Our tailored professional learning focuses on the issues that are important to you and your team. Bringing together the expertise of Griffith University’s academics and research centres, our professional learning is designed to deliver creative solutions for the workplace of tomorrow. Whether you are looking for opportunities for yourself, or your team we have you covered.

Advance your career with Griffith Professional

Griffith's new range of stackable professional courses designed to quickly upskill you for the future economy.