The case for an ‘impact economy’ brings together a number of progressive ideas, strategies and practices that are gaining traction and challenging the prevailing model of capitalism. In this article, we provide an introduction to the ‘impact economy’ (what, why and how), and highlight some considerations and issues for its development.

What is it?

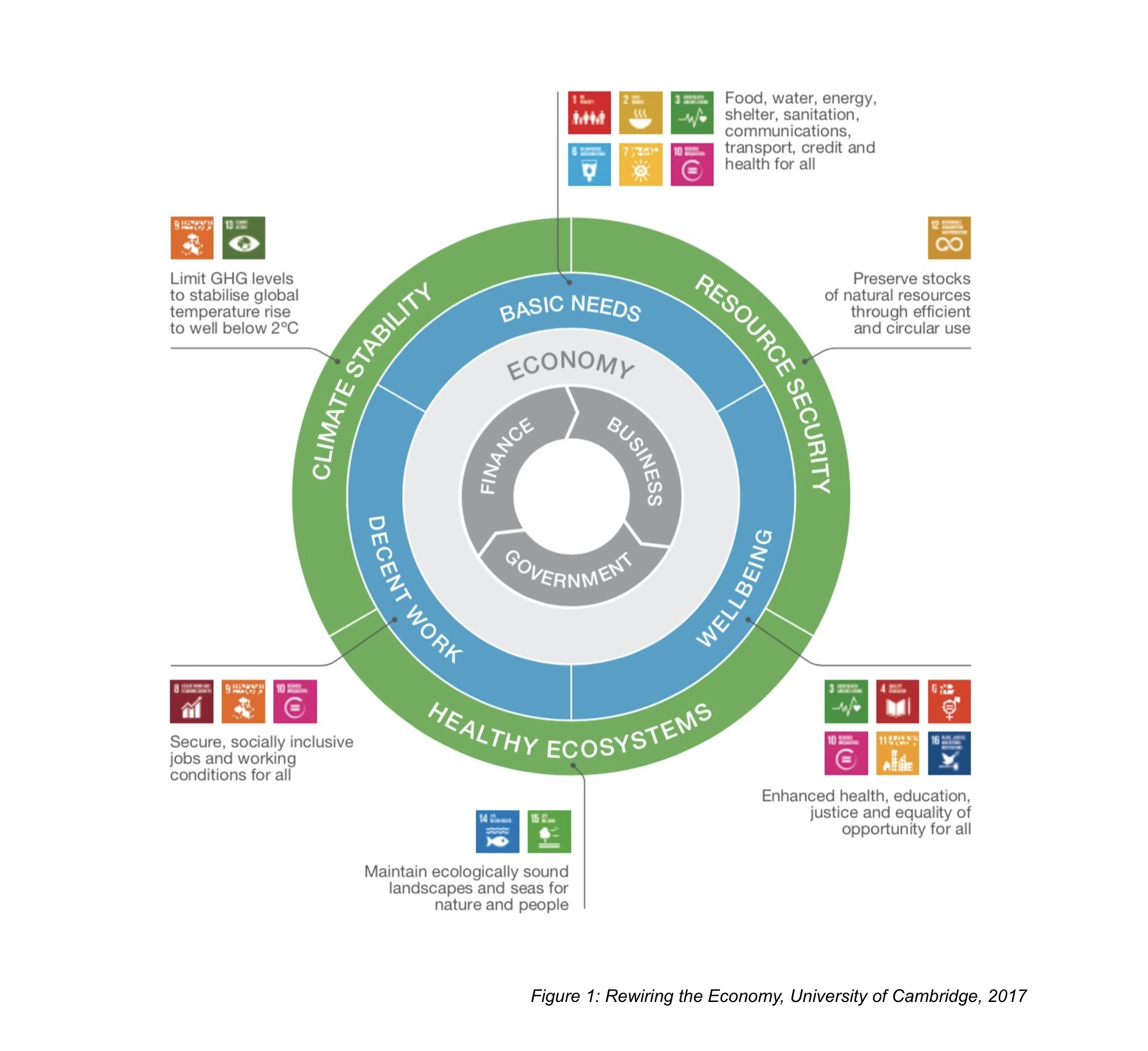

At its core, the concept of ‘impact economy’ is built on a holistic theory of how we create, exchange and distribute ‘value’, and also recognising the necessary interdependence of social, natural, human, manufactured and financial capitals in generating wealth and wellbeing1. The underlying logic is that a thriving and sustainable economy relies on a functional and stable society, which is in turn dependent on replenishable natural resources and healthy ecosystems. Regardless of how ‘free’ markets should be, they are anchored in a social context and a physical reality. The ‘impact economy’ signals it is time for our economic systems to ensure that what we value is directed towards the impacts we know will enable people, places and planet to thrive into the future. This is consequential now because we have created and entered ‘the Anthropocene’ – the first epoch in history where humans are fundamentally challenging the integrity of Earth's geology and ecosystems.

For humanity to thrive in this epoch, positive and negative externalities (the full costs and benefits) need to be better accounted for in all productive activities, with net positive impacts pursued in business and rewarded through trade, investment, taxation and labour. We need to establish a new economic narrative, and this needs to be reflected in governance structures, legal principles and policies (at company and government levels). It follows that our collective decision-making should intentionally seek to manage the health, balance and development of all capitals, rather than prioritising some at the expense of others. Given that it is estimated that the global economy is currently consuming resources at x1.75 the Earth’s carrying capacity, these shifts in mindset and behaviour are pertinent and pressing2.

To this point, the ‘impact economy’ is also a transformational proposition – it provides a strategic direction and an economic model that could enable us to address the big challenges of our time, and realise the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – 17 interconnected outcomes that, if achieved, offer long-term safety and prosperity for humanity.

Why now?

Around the world, and in Australia, the movement toward an impact economy is unfolding through a dynamic and organic interchange of ideas, missions, mechanisms, strategies and alliances. When we hear reference to the green new deal, impact investing, inclusive growth, purpose-led business, ethical consumption, social entrepreneurship, circular economy, community wealth building, or wellbeing budgets – they all represent approaches that feed into a broad intent (albeit from different perspectives) to integrate economic activity with improved social and environmental outcomes – an ‘impact economy’.

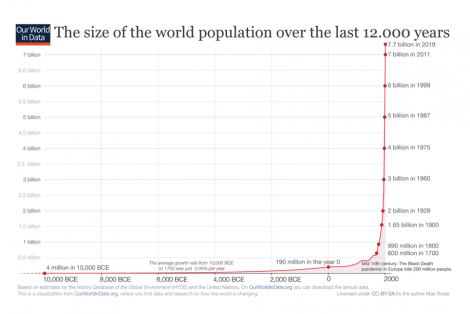

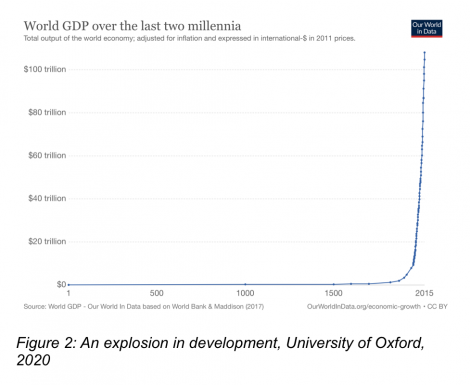

This movement (of movements) is emerging within a context of unprecedented and accelerating global change. It is easy to overlook the scale and pace of the change that we’re living through, but by reminding ourselves of just two data points – population growth and economic output (as currently measured) – we can see how the current period of development is nothing less than an explosion by any geological or historical timescale. These exponential trajectories are mirrored across any number of socio-economic and earth system trends.

These developments (the modern global economy) have created immeasurable gains for humanity (by historical standards), but they have also caused negative spillovers, unintended consequences and systemic risks that are now undermining future prospects for progress, safety and wellbeing. Considerable populations are now responding to this – the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer revealed that 56% of people (across 28 major and representative jurisdictions) believe that capitalism as it exists today is doing more harm than good, and that 73% desire change3. Be it in response to: climate change, growing inequality, precarious employment, environmental degradation, growing social unrest, stalling productivity, or the complex challenges and opportunities created by technological advancement; people, across sectors and geographies, are increasingly seeking to use their buying power, labour, savings, energy and ideas to facilitate a new economic model. At the heart of this, is an exploration of how value is created (and destroyed or appropriated) in a more systemic and connected ways.

“Everything we do affects people and the planet. Managing impact means figuring out which effects matter - and then trying to prevent the negative and increase the positive”. Impact Management Project.

By emphasising interdependence, the prevailing paradigm of economic growth is being challenged. More than ‘market imperfections’, the externalities of any given activity influence the prospects of others, while also affecting the viability of shared and enabling capitals. Put simply, focusing on GDP as a proxy for human progress without considering a wider range of indicators is like ‘running the world on a profit and loss statement without a balance sheet’4. New thinking is also calling for greater scrutiny on what actually constitutes ‘productive’ activity. In her influential work, Marianna Mazucatto makes the distinction between productive and extractive activity, and highlights the escalation of rent-seeking behaviours, especially in the financial industry, that go under the pretence of value creation. 5She argues that we have to think about the productive economy as more than the sum of individuals maximising their utility, and firms their profits, and understand it as a collective endeavour, where public and private value accrues (or diminishes) at multiple and connected levels.

How is the impact economy taking shape?

How does the impact economy actually work? Below we look at three core components of the economy – business, investment and trade – and provide examples of how this new thinking is taking shape.

Business

Debunking the idea that the purpose of business is maximising shareholder value, mainstream business is starting to redefine their role in society. This is poignantly demonstrated by the recent ‘Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation’ made by the US Business Roundtable, that articulates a fundamental commitment to all stakeholders and the environment.6 We are also seeing a proliferation of ‘impact enterprises’, organisations that intentionally set out to create social and environmental outcomes using business approaches. This is an eclectic group that operates in very different ways across all productive sectors. It includes: social enterprises, cooperatives, trading not-for-profits, community business, indigenous businesses and B Corps. These converging business movements of reform and revolution will continue to grow as younger generations demand more from their employers and prioritise societal impact in their own entrepreneurial endeavours.7 The question for the impact economy is how we make this movement more structural in nature (rather than driven by individuals and preference trends) and thereby create a strong signal that the merger of impact and commerce is a fundamental characteristic of value creation.

Investment

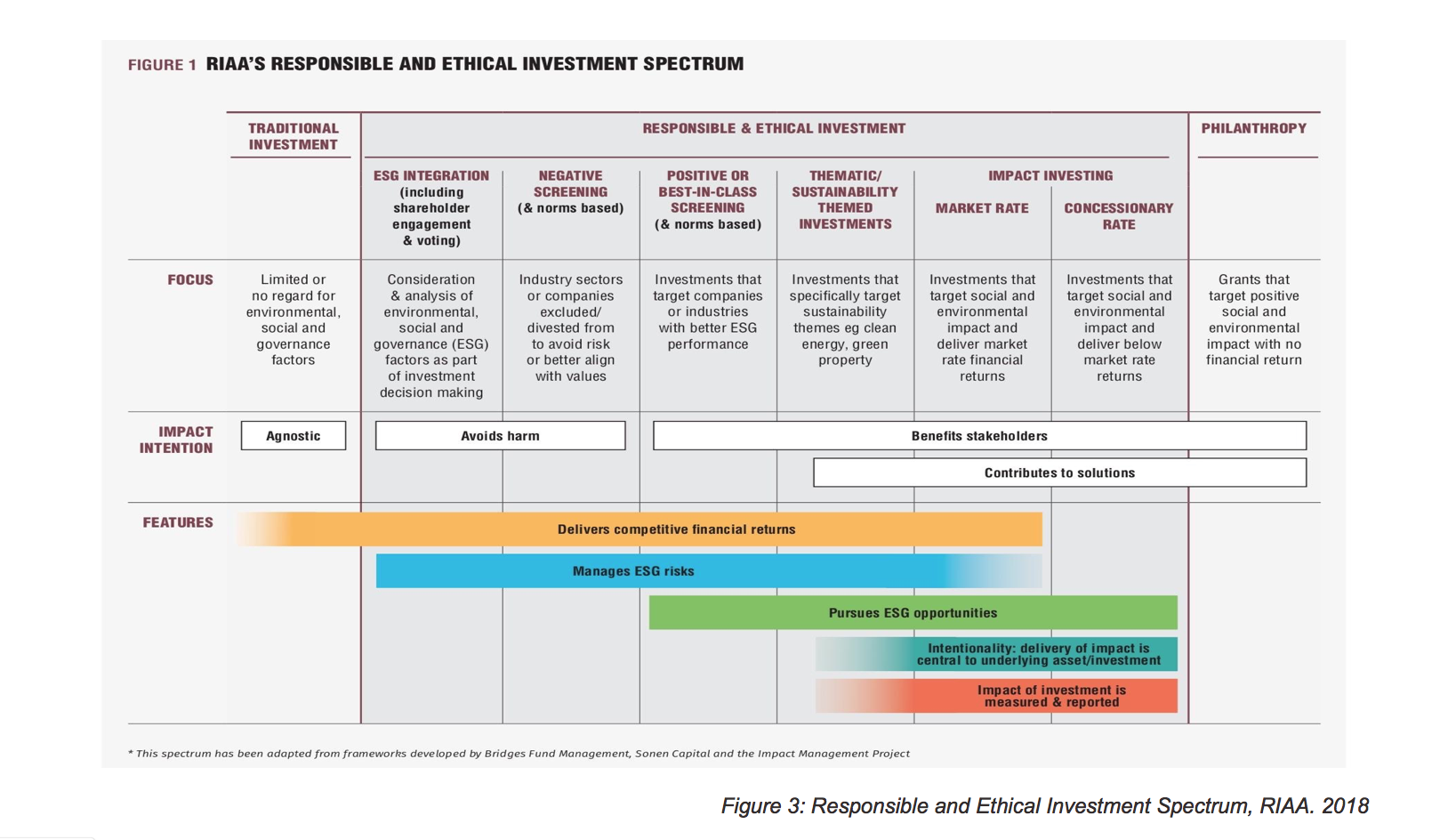

The purpose with which financial capital is invested has a profound effect on the nature of the outcomes it creates. Investment determines the direction of innovation, how resources are used, what value is created (and destroyed), and also how wealth is distributed, circulated and / or appropriated. Like the changing mindsets in mainstream business, there is a shift underway in investment strategies and practices.

These approaches spread along a continuum from ‘doing no harm’ (ESG / negative screening investments), to ‘creating more benefits’ (responsible / sustainable investments), to ‘intentionally targeting and measuring positive impacts’ (impact investments). In many cases the cost of capital is now being linked to the creation of positive impacts, incentivising the creation of societal benefits through individual transactions. Technology has also enabled the rise of crowdfunding, where customers, communities and values-aligned groups can finance new ventures through pooled investments. While the field is still emerging, early data points indicate that crowdfunding is unlocking significant new resources for activities that seek to make a positive impact, and is also democratising participation in investment and business ownership. This in turn is demonstrating how it is possible to co-create new forms of finance that are patiently and very intentionally seeking to contribute to certain outcomes and impacts. This is the challenge of the impact economy – to demonstrate in a myriad of ways how we can reapply economic tools to drive the capacity of actors, from across sectors, to create positive futures.

Trade

The flipside of how we invest, is how we spend. Our current economic narrative emphasises that purchasing preferences shape markets and demand, which in turn determines what productive activities are pursued and amplified. Many of the negative issues we face today are a result of artificially cheap products – which don’t factor in the cost of natural resources, labour exploitation, or waste. Like trends in investment, we are seeing shifts in consumer preferences, where buyers seek to reduce their negative footprint and reward businesses who maximise benefits for people, places and planet. How this is taken beyond trends and individual consumer preferences into structural signals, lies at the heart of the impact economy.

To this point, many governments are tightening regulations to improve standards throughout supply chains (mitigating a range of negative impact from carbon emissions to modern slavery). In addition, an increasing number of organisations are adopting voluntary measures (although mandated for public sector organisations in some jurisdictions) to unlock positive societal impacts through their procurement policies and practices – often known as ‘social procurement’. These developments are in turn expanding market opportunities for impact-driven businesses, and creating demand for more impact-aligned finance – a virtuous circle.

We are also seeing the development of wholly new markets, where the (positive or negative) impact is, itself, valued and transacted. Carbon markets are an early example of this, but other outcomes (such as jobs for the long-term unemployed, reduced recidivism, improved health etc.) are being incorporated into public sector commissioning and philanthropic financing mechanisms.

Considerations and issues for development

The shaping of the impact economy could evolve quickly over the next decade if we can create spaces in which to discuss, debate and demonstrate how it could work. What is needed to support its development is outlined below.

Growing political and policy leadership

While all sectors of society will play a critical role in progressing the impact economy, political direction and policy will have a massive effect on the scale and cohesion of uptake. Early leadership is being demonstrated by New Zealand, Iceland and Scotland, who established the ‘Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo)’ initiative in 2018. This alliance is focused on collaboration in pursuit of policy approaches that enhance wellbeing ‘through a broader understanding of economics’, and accelerating progress toward the SDGs.8 Policy direction is also being provided at a regional and city level. For example, in Australia, the ‘Advance Queensland’ economic development strategy emphasises support for businesses with ‘missions that matter’. These initiatives can be especially important in jurisdictions where national level leadership is not aligned with, or actively resistant to, progressive policy agendas.

Fostering Mission-led innovation

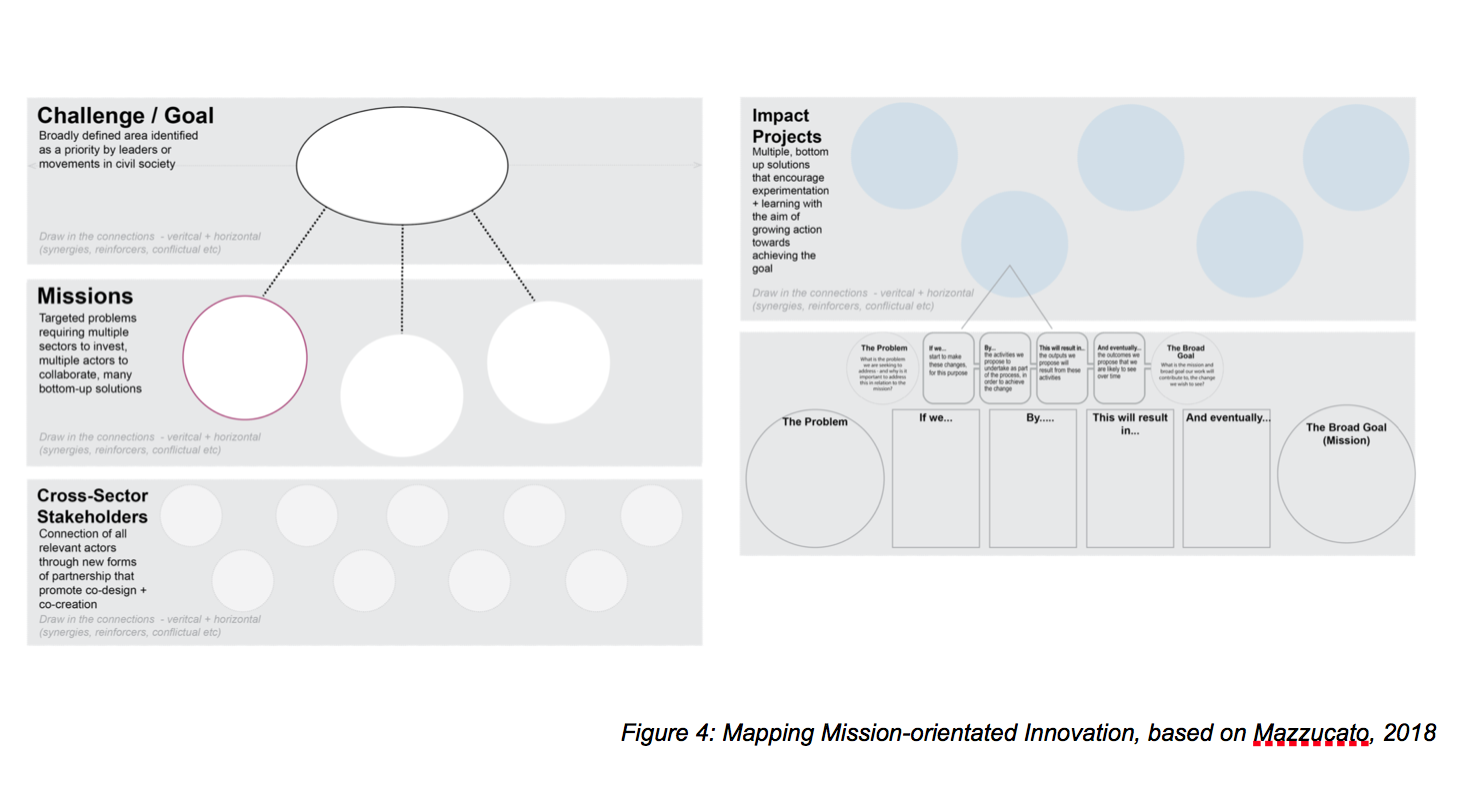

Innovating to tackle complex challenges is easier said than done. It requires intentionality, collaboration across sectors, and diverse and patient financial mechanisms. In essence, what is needed is innovation policy and practice that is ‘mission-led’. The underlying purpose of mission-led approaches is to scaffold the industrial strategies needed to rethink and tackle the big issues of our time. They also seek to mobilise collaboration and resources throughout the innovation chain – from research to implementation at scale. To succeed, these approaches require risk-taking and entrepreneurship from within the public sector, and a high degree of cooperation with the private sector and communities. Mapping out the array of innovation that will be needed to achieve the SDGs for instance, and investing in these across sectors, could spark the sorts of industrial strategies that will underpin growth in the impact economy. The map below provides a high level illustration of how such innovations could coalesce toward achieving goals such as the SDGs.

Framing, Accounting and Measuring Impact

Perhaps the biggest challenge in transitioning to an economy built on a more holistic system of value creation and capitals, is how to appraise, measure and account for ‘impact’. This manifests at both the level of individual transactions and organisational performance, and the level of national accounts and productivity.

At a jurisdictional level, new measures and indexes are being explored by both states (such as the WEGo alliance), and also multilateral institutions such as the Asian Development Bank with its ‘Green Growth Index’ (GGGI). For long-term coherence, it seems important that these approaches evolve to have some level of comparability, and aggregate within a globally shared framework such as the SDGs.

At a transaction, intervention and organisational level there are any number of measurement frameworks, tools, and approaches being employed. To name but a few, companies like Guayaki and Puma account for the value of rainfall and water use in their business models, the Global Steering Group on Impact Investment are making the case of ‘impact-linked accounts’, and the UK and New Zealand Governments have developed ‘unit cost’ databases for hundreds of outcomes. In addition, many organisations have adopted SROI, social accounting or social value methodologies, and the Impact Management Project provides an overarching framework for any given actor to work through a process of articulating and measuring the impact they intend to make.

It isn’t clear if there can ever be a universal approach to measurement, as the purpose and context of measurement are so varied. Also, while the prospect of standardisation is compelling, there are practical and conceptual risks in becoming overly technocratic and reductionist in the appraisal of impacts that are complex, long-term, and often reflect profound aspects of human experience. Rather than pursuing one overarching measurement system, priority should be given to increasing ‘impact literacy’ across professions. This would raise the collective capacity to design, track, evaluate and value impact in any number of situations, while also increasing the potential for more integrated impact management approaches to evolve over time.

Technology and inclusion

A great contention of the 21st Century will be how technology is advanced, deployed, owned and regulated – it will fundamentally shape how societies organise and the nature of the future global economy. In his recent book, Microsoft President Bruce Smith affirms the potential of technology to be used as both ‘a tool and a weapon’, calling for greater regulation and assurance that technology serves the whole of society, rather than just narrow interests. Issues that relate to ownership and access to data, regulation of content and platforms, and the underpinning purpose and ethics of the development and application of AI, are all pivotal issues that are ongoing and overlap with the prospects of an impact economy. This is particularly challenging as technology increasingly becomes an arms race between the US and China, neither of whom are currently putting citizens at the at the centres of their strategies.

Broader issues of inclusion also need to be addressed. While the impact economy could lead to a more equitable distribution of wealth and resources, its priority is to enable more people to actively, and creatively, participate in production. What’s more, there should be better recognition and reward for essential contributions that are not currently valued – such as caregiving, child-rearing and community organising. These reforms could take shape through: more distributed ownership of productive assets and organisations, diversification in who innovation services and supports aim to serve, narrowing the gap between those who have access to technology and those on the periphery, and greater recognition of diversity – including traditional and indigenous knowledge and cultures.

Wrapping up

The earliest records of humans trading goes back 120,000 years, where beaded shells were used as a proto-currency. There is a hypothesis that language evolved through trade, as people sought to negotiate the exchange of valuable goods and information.9 The economy has always been a central part of our cultural evolution and collective advancement.

However, the economy is a tool that works within a social and environmental context, and these contexts have changed radically since the prevailing paradigm of economy was constructed and took hold. The world we inhabit today is exponentially more complex, connected and crowded than it was 100 years ago, and the way we need to think about the economy – about productivity, value, markets, growth and capital(s) – requires an equally radical shake-up and restructure. By using the language of the ‘impact economy’ we are creating a container for the diversity of progressive work and thinking already underway, and to identify the issues that need further attention, exploration and reform by states, businesses, communities and individuals.

Ultimately, global and societal transformation is happening, one way or another, and we must determine both the nature of and the directions for the outcomes that we want. Positive outcomes are far from certain, and the 21st Century offers no end of challenges and risks. But agency and choice, for many of us, still remain an option. The impact economy argues for a positive future that includes all people, communities and places that thrive, and a planet on which diverse ecosystems can flourish.

Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation Co-Directors

As a society we find ourselves at a unique juncture of change, challenge and opportunity. Climate change, technology, the future of work, inequality, environmental strain, social unrest. It’s clear that new, holistic solutions, and progressive change are needed.

This is why the Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation exists. To equip you with the knowhow to navigate change and create positive societal impact. We are interested in how innovation and entrepreneurship can build inclusive and sustainable economies, and creative and cohesive communities.

Are you in? Visit us here

Alex Hannant

Prof Ingrid Burkett

Footnotes

1https://www.forumforthefuture.org/the-five-capitals

2https://www.footprintnetwork.org

3Edelman Trust Barometer 2020, Edelman

4First heard said by Sophie Haslem, Ākina Foundation Chair, in 2018

5The Value of Everything, Marianna Mazzucato, 2017

6The ‘Friedman Doctrine’ that became normative from the early 1970s

7The Deloitte Global Millennial Survey, 2019

8https://www.gov.scot/groups/wellbeing-economy-governments-wego/

9Transcendence: How Humans Evolved Through Fire, Language, Beauty, and Time, Gaia Vance, 2019

Professional Learning Hub

Our tailored professional learning focuses on the issues that are important to you and your team. Bringing together the expertise of Griffith University’s academics and research centres, our professional learning is designed to deliver creative solutions for the workplace of tomorrow. Whether you are looking for opportunities for yourself, or your team we have you covered.